Report: An anti-glossary for school mental health lessons, published 29 Aug 19

An anti-glossary for school mental health lessons – This article comes recommended from our colleagues in NHS Highland public health team.

Full article also available from here

29 August 2019

When delivering mental health lessons in schools, which will become mandatory from September 2020, the importance of the language used by teachers should not be underestimated.

Language both implicitly and explicitly reflects someone’s wider beliefs, attitudes, and opinions, as well as those of the school, and teachers tacitly set a precedent to the class. For some students, this will be the first time they have been given the opportunity to discuss mental health, making them likely to mirror the language introduced to them by teachers. For others with pre-existing knowledge, their vocabulary might reflect – through no fault of their own – the often insensitive language that is unfortunately all too common. In fact, 8 in 10 people surveyed by Mental Health Today expressed concerns about lessons containing “judgemental” content.

Language both implicitly and explicitly reflects someone’s wider beliefs, attitudes, and opinions, as well as those of the school, and teachers tacitly set a precedent to the class. For some students, this will be the first time they have been given the opportunity to discuss mental health, making them likely to mirror the language introduced to them by teachers. For others with pre-existing knowledge, their vocabulary might reflect – through no fault of their own – the often insensitive language that is unfortunately all too common. In fact, 8 in 10 people surveyed by Mental Health Today expressed concerns about lessons containing “judgemental” content.

With over 60 percent of readers calling for lessons to be shaped by the voices of lived experience, there is a desire for input from the very people who have experienced how language can be used to silence, blame, and shame people living with mental illness. Sensitive and inclusive language will foster an environment in which students feel psychologically safe: something which directly impacts whether they feel able to seek support.

Research by mental health charity Mind found the majority of school staff feel they “do not have enough information to support students with mental health”. Given the questionable tactics used in the government’s mental health education “consultation” – and the equally as questionable messages being promoted in its resource of choice – teachers’ apprehension comes as no surprise. Resources to support teachers in delivering these lessons tend to be littered with buzzwords that lack meaningful elaboration. These words, when examined critically, often have judgemental undertones. What does “resilience” really mean? Is it something we want to be presenting as the precursor to a “successful adult life”, as the Department for Education’s draft guidance claims?

It is brilliant that mental health lessons are becoming mandatory, but ill-informed and judgemental lessons could do more harm than having no lessons at all. Teachers are under no obligation to convey the messages promoted in the Department for Education’s guidance.

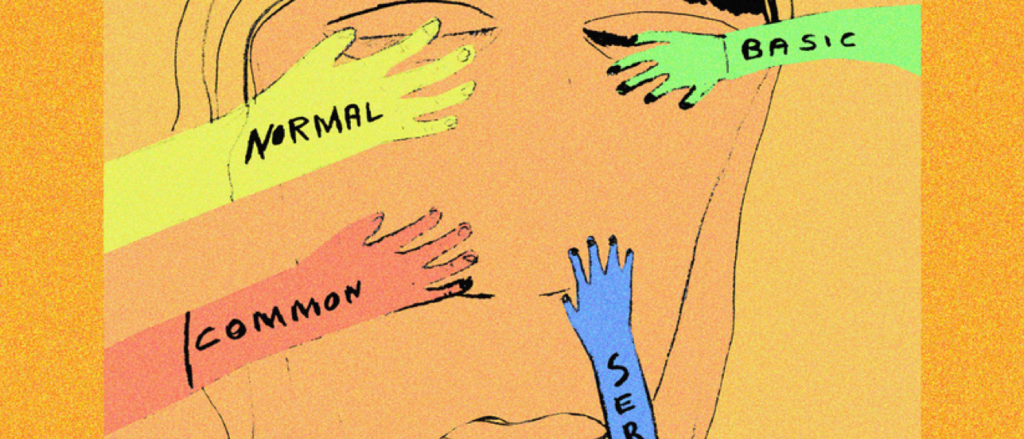

This “anti-glossary” explains why many expressions seen in plans for mental health classes are, at best, problematic and, at worst, deeply damaging. Most people do not use these words with bad intentions, but knowledge is power in mental health education. Language matters.

Common*+

Resources for teachers often label particular mental health challenges as “common”, usually anxiety and depression. All mental health issues are relatively common, so this distinction may discourage children/teenagers who experience other symptoms, especially those that are mistakenly deemed “rare”, from disclosing.

Rare

If children/teenagers are told that certain mental health conditions and symptoms are “rare”, it may mean that they feel ashamed to seek help, or dismiss their symptoms as something else with the belief that they are too “rare” for them to be experiencing.

Age-appropriate*

Because different children/teenagers mature at different ages, it is more helpful to discuss whether the delivery of topics is “age-appropriate” rather than the topics themselves. Making the delivery of topics “age-appropriate” may involve careful consideration of examples used, levels of description, and teaching method. Deeming entire topics as not being “age-appropriate” leads to unambitious lesson plans that may justify exclusion of topics, as has been seen with LGBTQI+ relationships education in some primary schools.

Ability to cope

This expression fails to recognise the influence of someone’s environment on their mental health, framing the “ability to cope” as a skill that can simply be taught or acquired through will alone. Coping mechanisms can be self-destructive, but are nonetheless suggestive of an “ability to cope” – this is problematic. The word “cope” sets the bar low for quality of life. Should children/teenagers be encouraged just to “cope” with mental health challenges, or can we support them in aiming higher? Instead of “ability to cope”, the phrase “capacity to process emotions/thoughts/feelings/experiences” suggests that every student is able to do so with the right support.

Ability to self-regulate*+

Presenting the “ability to self-regulate” as a determiner of success fails to recognise that people experience emotions and feelings differently. Experiencing emotions and feelings intensely is not necessarily a bad thing. However, if it causes a child/teenager distress, they should be encouraged to seek professional support. There are specific psychological therapies, such as Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), and Eye Movement Desensitisation Therapy (EMDR) that can assist someone in reducing the intensity of their emotions.

Acceptable and unacceptable behaviour*

In mental health education, children/teenagers are often capable of understanding more nuanced concepts than “acceptable and unacceptable behaviour”. Teachers should promote an understanding of how mental health issues can impact someone’s behaviour whilst reiterating that this does not absolve someone of responsibility. Instead of classifying behaviour by its “acceptability”, children/teenagers should be supported in gaining self-awareness of how their behaviour affects themselves and others, and where to seek professional support if behaviour they display themselves or witness from others makes them feel uncomfortable or unsafe.

Self-control*+

Advising teachers to educate children/teenagers about “self-control” can be interpreted in different ways. If it is with reference to drugs, alcohol, sex, and smoking, students should be informed about safety surrounding these activities and how to seek support if difficulties arise: not about “self-control”. In the context of displaying symptoms of mental health difficulties, the term “self-control” wrongly assumes that everyone is able to mask symptoms and, even if they are able to do so, this should not be encouraged. People experiencing mental health difficulties often feel embarrassed about displaying symptoms, and telling them to exercise control over them could reinforce this shame. For some, having to hide or “control” symptoms without professional support can be mentally – and even physically – taxing, and cause further distress. In the case of self-harm, it is not as simple as exercising “self-control”. There may be an interim period of recovery where someone is taught to harm in a safer way, while they transition to other forms of treatment and support. Teachers should also be mindful that impulsivity can be a symptom of multiple mental health disorders, when exhibited alongside other indicators.

Proportionate feelings/behaviour*+

This expression fails to recognise individual reactions and circumstances, comparing children/teenagers to a supposedly normative standard. Who dictates whether someone’s reactions or feelings are “proportionate”? Teachers should be mindful that often reactions are learned behaviours through parents/guardians such as aggression, and it can be just as helpful for teachers to model behaviours. Seemingly disproportionate feelings/behaviours may have once been adaptive to a student in certain situations and may continue to be. For example, “answering back” could have been necessary for a student in a different situation.

Self-respect*+

In guidance for teachers about mental health lessons, having healthy relationships is described as an indicator of “self-respect”. This implies that being in abusive relationships reflects a lack of “self-respect”, a damaging and untrue belief that will only shame and silence victims of abuse.

Virtues*

There is an undeniable religious undertone to this word. Teachers could use the more neutral word “values” and encourage children/teenagers to discover their own rather than impose a “standardised” set upon them.

Healthy family life*

Telling students about the characteristics of a “healthy family life” may be harmful to the many whose families do not fit this ideal, such as children/teenagers in care. It imposes normative values upon students, and illuminates a “healthy family life” as being necessary for someone to live a good life. If children/teenagers are told that their family is dysfunctional, what are they expected to do with this information? This puts to onus on them to change circumstances that are more often than not beyond their control. However, students must be made aware that there is a variety of support available to them if aspects of their home life are causing distress or if they experience feelings of being unsafe.

Not looking after themselves

This phrase is used in different contexts: in relation to mental health, physical health, and safeguarding. From someone avoiding washing due to sensory preferences, to unclean clothes because of limited access to laundry facilities, to putting themselves in unsafe sexual situations to re-enact past traumas, there are a whole range of reasons why someone might be perceived to be “not looking after themselves”. Teachers should exercise judgement as to whether this expression will encourage compassion or, instead, engender bullying and judgement through drawing attention to students’ appearances, hygiene, and behaviour. In a safeguarding context, using the phrase “not looking after themselves” puts the onus on children/teenagers to “keep themselves safe”, a damaging message that is a form of victim blaming. Instead, children/teenagers should be educated about different forms of abuse. Alongside offering support and signposting to other agencies, teachers must reassure students that abuse is never their fault and was not caused by their inability to “look after themselves”.

Attention seeking

The problem with “attention seeking” lies not in the phrase itself but in the way it is used. Often used in relation to suicide and self-ham to suggest an element of intentional manipulation, it devalidates and diminishes a person’s distress. We all need attention: at different times, and some people more than others. If a child/teenager acts in a way that is perceived to be “attention seeking”, teachers should be compassionate rather than dismissive. This may be through taking any concerns raised seriously, and signposting them to support such as:

- Living with and recovering from self-harm

- I have experienced or witnessed something traumatic

- Childline

Resilience*+

The “resilience” narrative obscures the wider causes and solutions for children’s mental health. Positing “resilience” as something that can simply be taught if someone does not innately possess it fails to recognise how students’ experiences and environment affect their mental health. For children/teenagers living with poverty and abuse, trying to make them “resilient” can unfairly place the onus on them to deal with something that should not be happening to them. It can also ignore the ways in which many children are already incredibly “resilient”, having dealt with trauma and experiences that would floor many adults.

Serious mental health conditions*+

All mental health conditions are serious. Deeming some to be “serious” implicitly creates a hierarchy whereby people living with particular conditions are viewed as being less worthy of support.

Suicide is selfish

When someone feels suicidal, they may agonise over how it would affect their loved ones. Suicide is never a thoughtless act.

Going crazy/mad

The phrase “you’re not going crazy/mad” is often used with the intention to reassure someone of their sanity. This begs the question: who, then, is actually “going crazy/mad”? Is it people whose mental health issues present in a way that is frightening or upsetting to others? Telling children/teenagers that their experiences are valid and that there is support available is another way of validating their difficulties without inadvertently perpetuating stigma towards some conditions.

Abnormal beliefs

Often used in the content of psychosis, this suggests that people with beliefs that may contradict other people’s beliefs and realities are “abnormal”. People who hold such beliefs do not necessarily perceive them as “abnormal”, and calling them this in a classroom environment may invalidate their experiences and cause further distress. Labelling these beliefs “abnormal” implies that they are uncommon. In fact, many people experience delusions and overvalued beliefs, and there is specific support available if these beliefs cause distress.

Warning signs

“Warning signs” is used to denote symptoms or behaviours that precede or constitute mental illness. The word “warning” suggests that the “signs” are always both obvious and harmful to someone, be it the person themselves or others. This is misleading, especially when discussing experiences of mania. Teachers could use “indicators” in the place of “warning signs”, and reiterate that there is not necessarily a set list of indicators and that they vary between people and conditions.

Treatment resistant

The term “treatment resistant” is damaging as it suggests that recovery is sometimes unattainable. “Resistant” implies a conscious effort not to succeed in treatment, and shames children/teenagers who engage in treatment without noticing a marked improvement. Teachers should be telling students that everyone can have a better quality of life if given the right support.

Productive*

Telling children/teenagers that their self-worth is necessarily linked to productivity is ableist, for it fails to acknowledges students’ individual circumstances. Placing emphasis on “productivity” assumes that everyone is not only physically, mentally, and intellectually capable of being “productive” at all times, but also that “productivity” is beneficial to their wellbeing. Whilst some may find being “productive” is useful in improving their mental health, others will be unable to be “productive” even if they want to and so will not have the opportunity to reap potential benefits. Being “productive” is not an adequate substitute for support and psychological treatment, and some students may see a decline in their health when trying to reach normative standards of productivity, and those who are unable to do so could feel ashamed and inadequate. Teachers should highlight that everyone has different circumstances that impact their life and health, and that self-worth should not be defined by how “productive” someone is.

Successful adult life*

It is not the place of schools – or teachers – to impose or pass judgement about how to live a “successful adult life”. The word “successful” introduces an element of competition to students, implying that some in the classroom will inevitably grow up to become “failures”. Children/teenagers should be encouraged to discover for themselves what their values are and what living their best life would look like.

* expression is used in the Department for Education’s draft guidance

+ expression is used in the PSHE Association’s guidance for teachers